Because it matters

Making things happen, making things right, because it matters.

Are you getting the Test Pyramid wrong?

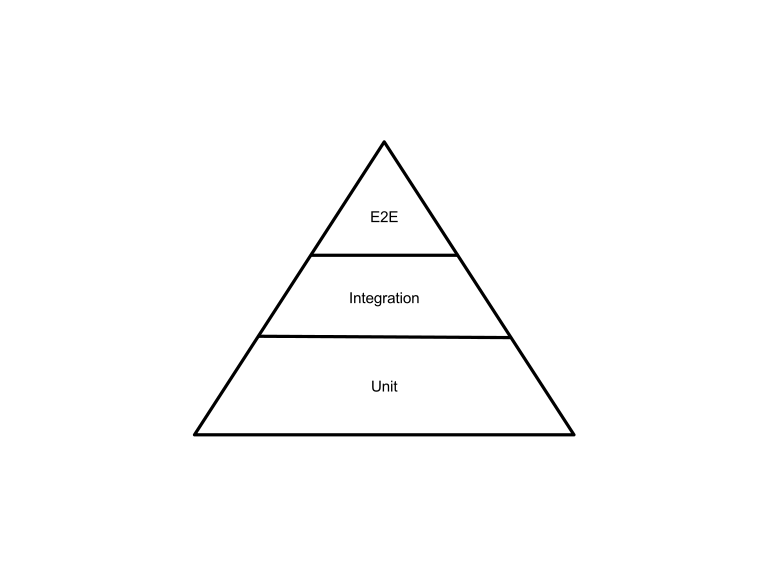

The Test Pyramid has been and is still a popular “go-to” testing strategy since Mike Cohn introduced it in his book Succeeding with Agile in 2009. It emphasises the importance of writing a large number of unit tests, a smaller number of integration tests, and an even smaller number of end-to-end tests. The Test Pyramid is a great idea, and many developers and teams have used it to improve the quality of their software. However, some developers have taken the Test Pyramid too far. For example, some developers now write unit tests for every function or every single line of code. Some teams started to require a minimum test coverage for commits, which, in many organisations, is usually between 80–90%. People are proud of having high test coverage and a (false) sense of confidence in the correctness of the software simply because of that. Recently, I’ve been hearing more and more developers complain that unit testing is more trouble than it’s worth. Some readers of my article from four years ago even argue that end-to-end tests are more valuable than unit tests. These engineers are frustrated by the need to create tons of mocks in their unit tests, and by the amount of time they spend rewriting tests when they refactor their application code. In some cases, they end up writing more test code than application code, which is a nightmare.

Why do some developers struggle with writing effective unit tests and implementing the Test Pyramid?

The paradigm shift

In the old days, object-oriented programming (OOP) was the go-to paradigm for small-scale, monolithic applications. But as applications grew larger and more complex, OOP started to show its cracks. Abstraction, encapsulation, inheritance, and polymorphism became increasingly difficult to comprehend and manage. Developers wanted something easier to read, understand, test, and reuse. That’s when JavaScript started to gain popularity, functional programming rose to fame, and microservice architectures became the de facto standard for backend software design. And that’s also when the definition of a “unit” in unit testing became blurry.

Back when everything was modelled in a 3-layer monolithic architecture, an object-oriented class, which is typically a business entity, was often treated as a unit. Developers would write unit tests to verify the object’s behaviours, which were likely to be the business behaviours. In procedural or functional programming, a single function is often considered a unit. But in a world dominated by microservices, such a function could sometimes be trivial, like mutating a JSON field, storing the updated data in a database, and then producing a Kafka event. It usually doesn’t make any business sense on its own and relies on other parts of the system to create the expected business behaviours.

How some developers write unit tests

Let’s consider an example I’ve seen while working for a client who is one of the largest banks in the world. The code below is a (simplified) Spring Boot service that downloads an XML file from a partner service, parses and transforms it to a JSON object, stores the object attributes in a database, and then produces a Kafka event containing the transformed data.

@Component

public class XyzReportProcessingService {

private final ReportDownloader reportDownloader;

private final ReportStorageService reportStorageService;

private final ReportProcessor reportProcessor;

...

public void process(ReportMetadata metadata) {

...

downloadReport(metadata).fold(

logError(),

downloadedReport -> {

storeReportAndPublishEvent(reportProcessor).apply(downloadedReport);

return null;

}

);

}

private Either<DownloadError, Report> downloadReport(ReportMetadata metadata) {

return reportDownloader.downloadXmlReport(metadata.getReportId())

.map(contents -> new Report(metadata.getReportId(), contents));

}

private Function<Report, Void> storeReportAndPublishEvent(ReportProcessor reportProcessor) {

return report -> {

storeReport(report);

reportProcessor.unmarshallAndPublishEvent(report);

return null;

};

}

private void storeReport(Report report) {

var contents = new String(report.reportContents().contents(), StandardCharsets.UTF_8);

reportStorageService.storeReport(report.reportId(), new JsonObject(contents));

}

...

}

The ReportDownloader uses a RestTemplate from the Spring Framework to download an XML report file from a partner service. The ReportStorageService is an interface. Its implementation is responsible for persisting the data to a database. The ReportProcessor uses KafkaTemplate from the Spring Framework to publish a Kafka event.

The unit test for the ReportDownloader looks something like this:

@ExtendWith(MockitoExtension.class)

class ReportDownloaderTest {

@Mock

private RestTemplate restTemplate;

private ReportDownloader underTest;

...

@BeforeEach

void setUp() {

when(restTemplate.getUriTemplateHandler()).thenReturn(new DefaultUriBuilderFactory());

var apiClient = new ApiClient(restTemplate);

underTest = new ReportDownloader(new ReportsApi(apiClient));

}

@Test

void testDownloadReport() throws URISyntaxException {

// Set up a mocked report API response object

var reportResponse = ...

when(restTemplate.exchange(ArgumentMatchers.<?>any(), ArgumentMatchers.<ParameterizedTypeReference<?>>any())).thenAnswer(call -> {

var entity = call.getArgument(0, RequestEntity.class);

// Check the report ID

...

// Check the requested content type

...

return new ResponseEntity<>(reportResponse, HttpStatus.OK);

});

var response = underTest.downloadReport(reportId);

assertThat(response.isRight()).isTrue();

assertThat(response.get().contentType()).isEqualTo(MediaType.APPLICATION_XML);

assertThat(new String(response.get().contents()).isEqualTo("...");

}

}

The unit test for the ReportStorageService might look like this:

@ExtendWith(MockitoExtension.class)

class ReportStorageServiceTest {

@Mock

private ReportObjectToReportEntityMapper mapper;

@Mock

private ReportEntityRepository repository;

private ReportStorageService underTest = new ReportStorageServiceImpl(mapper, repository);

...

@Test

void testStoreReport() {

var captor = ArgumentCaptor.forClass(ReportEntity.class);

var report = ...

var entity = ...

when(mapper.map(any())).thenReturn(entity);

underTest.storeReport(mapper.map(report));

verify(repository, times(1)).save(captor.capture());

var capturedEntity = captor.getValue();

assertThat(capturedEntity.getId()).isNotNull();

// Assert all entity fields

...

}

}

Why is this bad?

We have mocked everything except our “unit”, and we’re asserting almost everything possible. The tests are passing, and the application code is working fine. So why is this bad?

Let’s take a closer look at the ReportDownloaderTest. First, the RestTemplate.exchange() method has many overloaded versions, but we’re only mocking one of them. This works because we rely on our knowledge of the implementation details. We know that we called a specific RestTemplate.exchange() method. But this is fragile and it would break easily. Second, the test requires us to mock the RestTemplate.getUriTemplateHandler() method, which is used by the Spring Framework internally and not directly by the application code. So we’re mocking something that doesn’t belong to us. Third, by mocking RestTemplate methods, we’re essentially writing more test code than application code. This is a waste of time and effort, and it makes the tests more difficult to maintain.

In the ReportStorageServiceTest, we’ve mocked our repository and verified that its save() method is called. This is not ideal because we’re testing the interactions, not the behaviours. In other words, we’re testing that the code calls the save() method, but we’re not testing that the save() method actually persists in the data in the database. This can lead to two problems:

- The test can pass even if the application code breaks. For example, if the

save()method throws an exception, the test will still pass because it only verifies that thesave()method is called. - The test can break even if the application code works. For example, if someone refactors the code to call the

saveAll()method instead, the test will break because it’s expecting thesave()method to be called.What to do instead

Instead of mocking the

RestTemplateclass, why don’t we use a fake web server that returns predefined responses? TheMockRestServiceServerclass from the Spring Framework does just that. With much fewer lines of code, we can configure it to return specific responses, without the need for lengthy mocking logic.

In the ReportStorageServiceTest, we should care about what matters: is the entity persisted in the repository? We shouldn’t get bogged down in how it’s persisted, whether it’s by using the repository.save() or some other method. Verifying the states changed rather than the interactions invoked frees us from testing against the implementation details. This means we don’t have to rewrite our tests every time we refactor our code. In this particular example, we can use the @DataJpaTest annotation and the TestEntityManager class to verify the database state without mocking anything.

What about speed?

Some developers might argue that avoiding mocks in unit tests makes them slower. But have they become religious about how fast their unit tests should run? Some insist that unit tests must finish within sub-seconds. So far, I’ve suggested using fakes over mocks in unit tests to simulate behaviours and verify state changes. Apparently, this approach is slower than using mocks and verifying the interactions, but it would still finish within seconds. So let’s say it’s ten times slower. But does that really mean it is slow, and should we avoid it because of that?

Let’s revisit the Test Pyramid. We write a large number of unit tests because they are the cheapest to create and the fastest to give us feedback. But that’s not the point. The point is that unit tests provide the most value compared to other types of tests. They’re worth creating and running, even if they take seconds to run. If a unit test can ensure the correctness of some complex application code, it’s worth running, regardless of how long it takes as long as it is within seconds. On the other hand, if a unit test takes only sub-seconds to run but doesn’t give us much confidence in the correctness of the behaviours, it’s not worth creating in the first place.

But these are integration tests, not unit tests

Some developers argue that avoiding mocks in unit tests violates the principles of the Test Pyramid because it essentially turns unit tests into integration tests.

I disagree. It depends on how you define a “unit”. Back in the era of big monolithic applications, developers often worked on separate modules. Sometimes, a single developer would create an entire module. They wrote unit tests to verify the business behaviours of an individual module and integration tests to verify the combined behaviours of multiple modules and the interactions between them. In a modern microservice-based application, a single business operation often involves multiple microservices. This means that unit tests can no longer be used to verify meaningful business logic. Instead, unit tests are only used to verify implementation details, and integration tests are used to do what unit tests used to do.

This article would make sense if we define a “unit” as the smallest scope of business logic. Under this definition, an integration test would involve testing two or more business operations combined. But what if we took a more generic, value-based approach?

The tests at the bottom of the Test Pyramid should be the cheapest to create, not too slow to run, and give us some confidence in the application’s correctness. The tests in the middle of the Test Pyramid might be slightly more expensive to create, and a bit slower to run, but give us higher confidence. This definition doesn’t interpret the meaning of “unit” or “integration”. It’s unfortunate how the layers of the Test Pyramid are named because it confuses developers even after its introduction a decade later.

Summary

How do you write meaningful unit tests and implement the Test Pyramid effectively? Here are the key takeaways:

- Avoid using mocks whenever practical. Mocking couples your tests to your application code, making them fragile and difficult to maintain.

- Use the Test-Driven Development (TDD) approach. TDD forces you to think about the behavioural design of your code before you write it, and it helps you avoid writing unnecessary tests.

- Use fake data or services to simulate application behaviours instead of using mocks. Fake data and services make your tests more independent and reliable than using mocks.

- Focus on state changes, not interactions. Instead of testing how your code interacts with other objects, test how it changes the state of the world. This will make your tests more robust and less likely to break when you refactor your code.

- Write unit tests that are easy to maintain. When you refactor your code, your unit tests should be the easiest thing to update. If you have to spend a lot of time rewriting your tests, then you’re doing something wrong.

- Don’t be afraid to use external resources in your unit tests. If you need to mock a dependency or use a fake service to test your code, that’s okay. Don’t let anyone tell you that your unit tests are slow just because they involve other “units”.

- Define “unit” in a way that benefits the most in your context. The traditional definition of a “unit” is a class, but in a microservice-based application, a unit might be a small business operation. Choose a definition that makes sense for your team and your code.

- Make sure your tests don’t give false-positive or false-negative results. False positives and false negatives can waste your time and lead to bugs in your code. Make sure your tests are well-designed and cover all possible scenarios.

- Focus on the business value of the Test Pyramid, not the naming of the layers. The Test Pyramid is all about writing tests that give you the most confidence in your code, regardless of whether they’re called “unit tests” or “integration tests”.

- High test coverage doesn’t guarantee a bug-free application. If your tests are verifying the wrong things, they won’t catch the bugs that matter. Make sure your tests are focused on the things that are most important to your business.