Because it matters

Making things happen, making things right, because it matters.

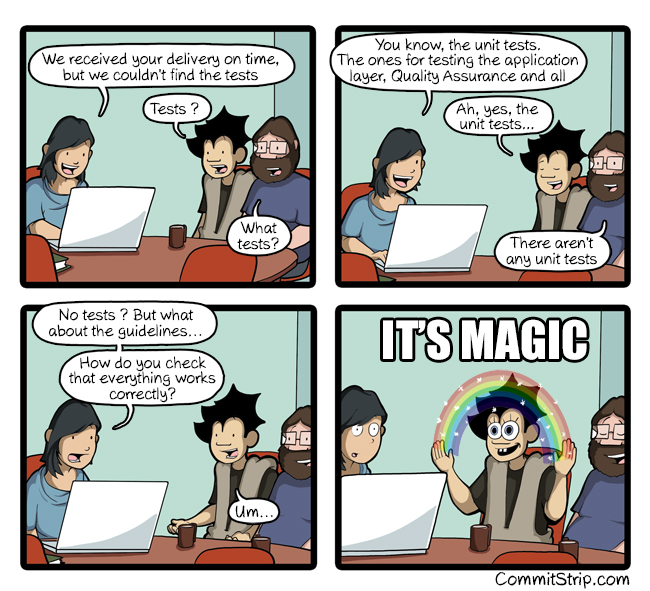

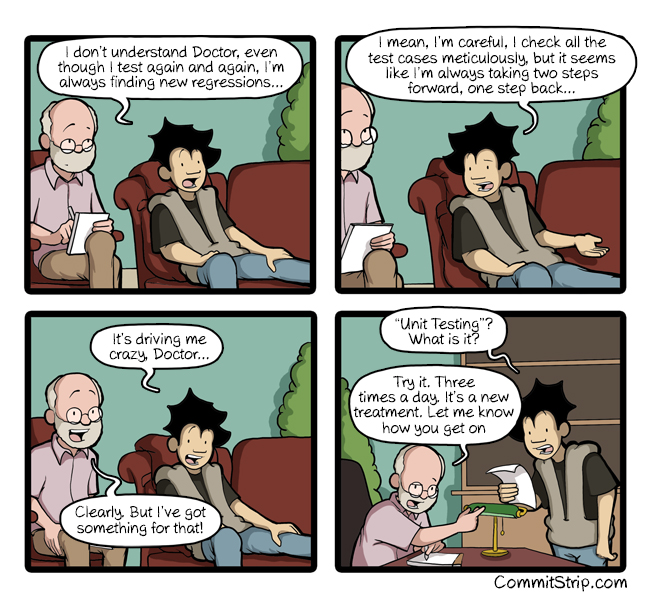

Why don’t developers use TDD in practice

How to make TDD great again

Like everything that comes under the name of Agile, Test Driven Development (TDD) is something that sounds great in theory. In practice, it is unclear how to do it right. You are often told that if you don’t like it, you are doing it wrong. It comes as no surprise that most developers I’ve met could explain the benefits of using TDD while none of them used it in their work. Not a single one.

Lately, there have been voices against TDD, blaming it not worth the effort and not keeping many of its promises. Some even claim that TDD is dead. How could something so advantageous is so unwelcome to developers?

In this article, I want to talk about four major problems with TDD in practice that explain this phenomenon.

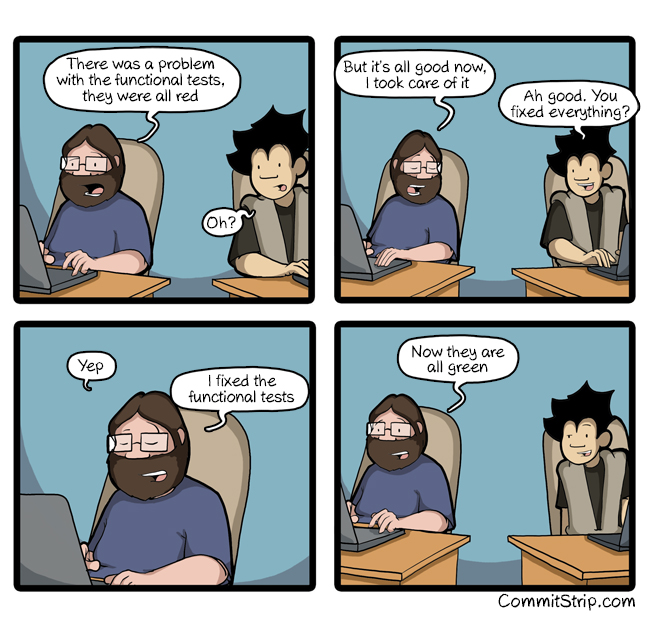

Problem 1: Refactoring breaks many tests

If we make a small change to the implementation code, none of the tests would break. That is one of the promises that TDD makes. In practice, at least a thousand tests break. Something that should not happen happened. To fix that, we often rewrite, not refactor, our test code. We spend a lot more time writing test code than the implementation code.

In the end, we doubt if it is worth rewriting the test code if we are sure we will refactor the implementation code. Can we write fewer tests? Can we skip all the tests? Then, someone will suggest writing tests when all changes are made, like the day before release. In practice, it is often after release, or never.

Problem 2: Writing more test code than implementation code

To test a “unit” of the implementation code, we often write tests for all public methods and write mocks for dependencies. Sometimes we make private methods public because otherwise there is no way to increase our code coverage. We create test cases to cover as many different flows of the implementation code as possible.

We end up being unproductive as we write more test code than the implementation code. Tests will not be released and delivered to users. It makes more sense to skip tests as it seems to speed up development.

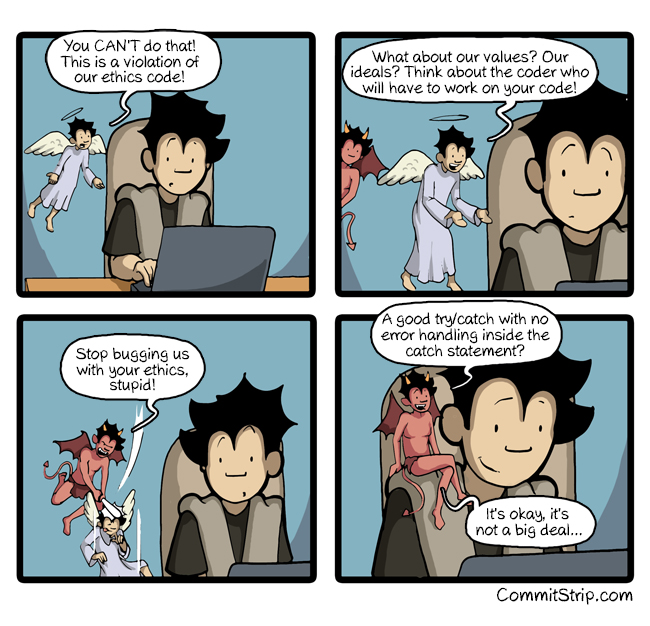

Problem 3: Red-Green-Refactor encourages writing bad code

In a nutshell, Red-Green-Refactor means:

- Write a test that fails, or doesn’t even compile

- Write just enough implementation code to make the test pass

- Refactor the implementation code

This approach could be problematic, especially to senior developers, because this is what it really means in practice:

- Write a test that fails, or doesn’t even compile

- Write bad code to make the test pass, bad code that violates best practices

- Refactor the bad code and rewrite, not refactor, the tests

This destroys our values as developers. It is almost a violation of programming ethics, illegal and unprofessional.

Problem 4: Code coverage measurement

It is an old saying, “What gets measured gets done.” If quality is measured by code coverage, developers will try every attempts to meet that minimum code coverage requirement. If we are not allowed to ship when code coverage is below 85%, we will end up adding more and more tests, usually those easiest to create, to make it just over 85% and no more. Ironically, most of these tests are trivial and without much value to ensure quality. It shifts developer to focus on finding ways to create low-quality tests just to hit the minimum code coverage target.

Making TDD great again

TDD tutorial materials may be to blame for part of the problems. Most of them focus on overly simplified examples, such as:

- Adding two integers

- Concatenate strings

- FizzBuzz

In those examples, it is often unclear what a unit test should look like in TDD. How to test a Spring Boot application? What about testing Object-Oriented code? Developers tend to believe that they need to test every “unit” of their code — every public method. This means the following problems in such a TDD approach:

- More test code than the implementation code

- Not easy to design tests before the implementation is done

- Implementation refactoring breaks existing tests

Kent Beck explained in his book, Test Driven Development: By Example, that unit tests in TDD should test for behaviors, not implementations. After nearly 20 years later, most of the TDD articles have forgotten about this original idea. Developers often go too far trying to write tests for everything. Seeing that his idea has caused so much confusion and people started to complain about their pain using TDD, Kent Beck elaborated further how he would use unit tests for.

In other words, we should test the behavior of our program, or the “API” boundaries within our program. A “unit” usually refers to one meaningful behavior in our software design, not software implementation. This solves problems 1, 2 and 3 above because implementations change frequently during development but not behaviors.

For the last problem about code coverage could be solved easily if we understand its meaning behind — to help developers find untested code. Code coverage has nothing to do with code quality, which can be proven statistically. The percentage simply means nothing. The meaningful part of a coverage report is that it tells us what code is not yet tested and it could be buggy potentially. Again, Kent Beck would only test the code that might be buggy.

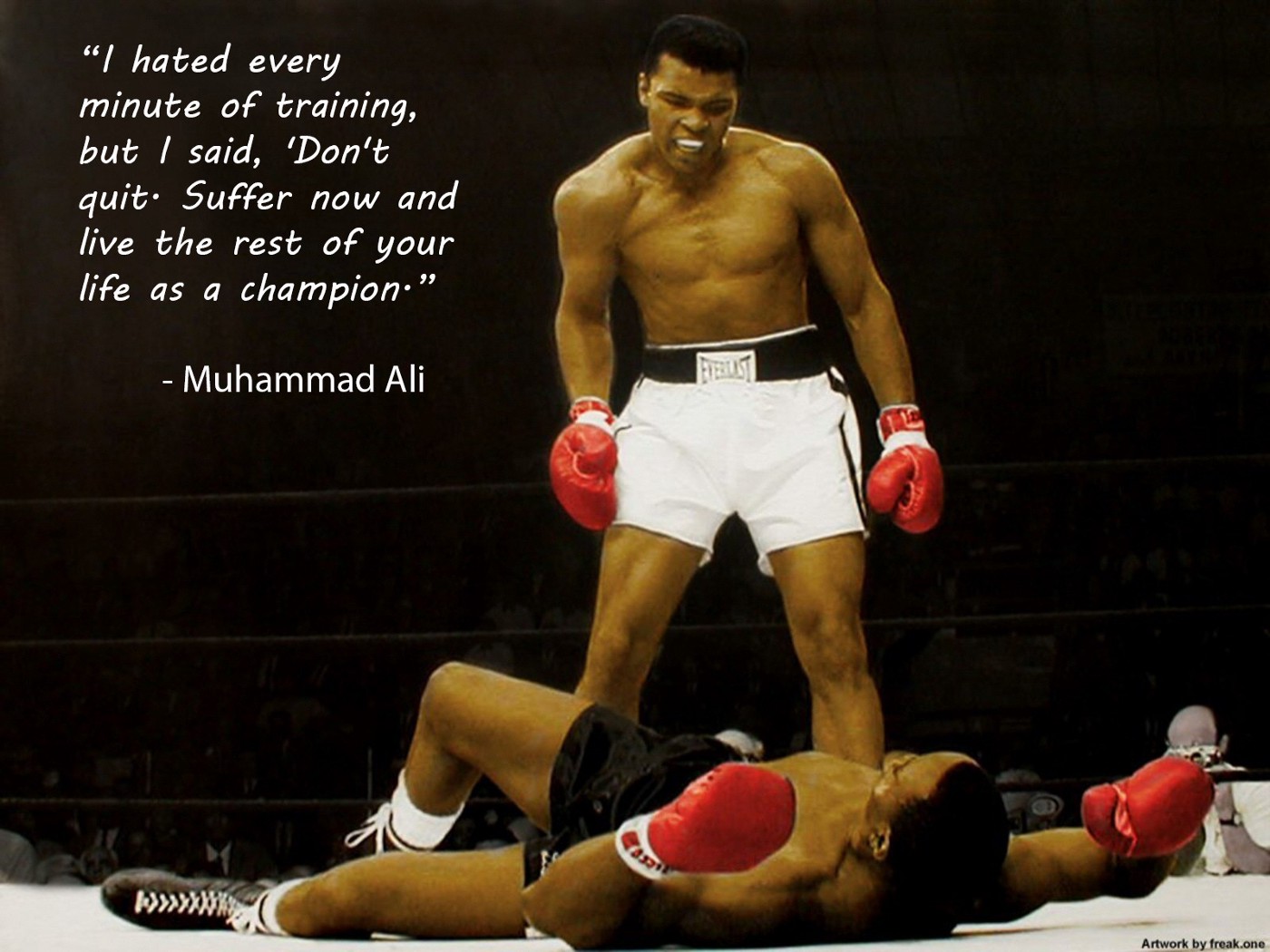

TDD as a habit

Unit testing, and a lot of other Agile terminology, is like going to the gym. You know it is good for you, all the arguments make sense, so you start working out. You are so motivated initially, which is great, but after a few days of exercise, you start to rethink if it is worth the effort. You are spending an hour a day to change your clothes and run like a hamster. Yet you are not sure if you are really getting anything other than sore legs and arms.

Then, after a week or two, just as the soreness is about to go away, a project deadline beings approaching. You need to spend every waking hour trying to get meaningful work done, so you cut out irrelevant stuff, like going to the gym. Now the deadline is over, but you fall out of the habit. If you manage to make it back to the gym at all, you feel just as sore as you were the first time you went.

You do some reading and observe others, to see if you are doing something wrong. You being to feel a bit confused about why those happy people praising the virtues of exercise. You realize that you don’t have a lot in common. They don’t have to walk 15 minutes out of the way to the gym; there is one in their building. They don’t have to argue with anybody about the benefits of exercise; it is just something everybody does. When a project deadline approaches, no one would tell them that exercise is unnecessary, just as your boss would not ask you to stop eating.

Now, start practicing TDD in your work and when in doubt, read the book again.