Because it matters

Making things happen, making things right, because it matters.

84% of all integration projects failed. This is what I did to integrate unknown systems and avoided common problems.

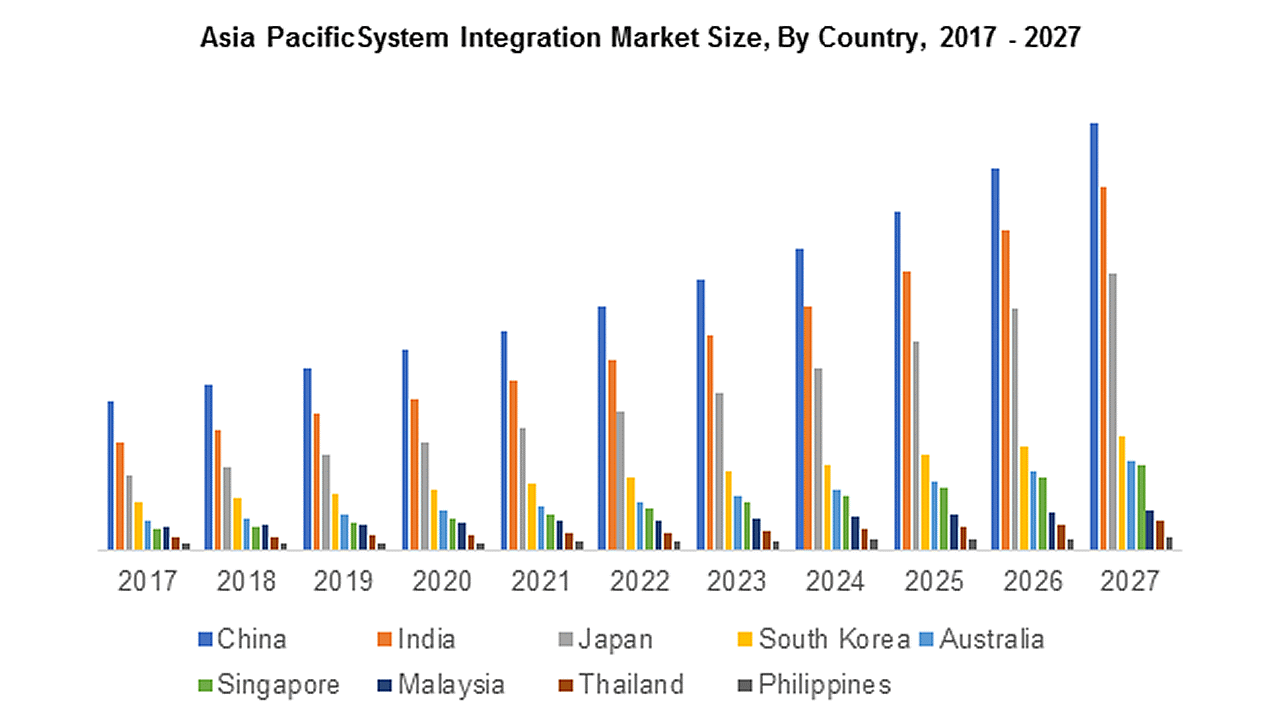

IT projects often cost more, take a longer time, and have fewer benefits than planned. According to some studies (Forbes 2016; BCG 2020), as many as 70-84% of all digital transformation efforts ended in partial or total failure. Research has shown that large projects having a large amount of information that requires integration have a failure rate 50% higher than small projects. A McKinsey-Oxford study reported in 2012 that 17% of those large projects had gone so badly that they threatened the very existence of the organisations. Again and again, it resonates consistently across industries and domains with fellow engineers, architects, project managers and business stakeholders, and not for good reasons.

What is system integration? Why do businesses need it?

System integration is the process of connecting multiple individual sub-systems, applications, or services, into a single larger system that functions as one unit. In recent years, IT systems have become an important competitive element in many industries. Systems and applications are getting bigger, with new functionalities developed every day, touching more parts of the organisation. System integration is becoming increasingly significant and a premier requirement for evolving the business, and improving productivity, quality, and efficiency of business operations. It poses major risks to the company if the system integration process doesn’t go as planned.

Why do integration projects fail?

Integration projects have a terrible reputation for failing. It only takes a few missteps to botch up the whole thing. Various factors may lead to failures, and the reasons I mentioned here are by no means exhaustive. Nevertheless, it is essential to understand the commonly mentioned reasons and make sure nothing stands in your way to success.

Unclear scope

It should go without saying that if your integration project doesn’t have clear, specific, and achievable goals and timelines, it will fail with the allocated budget and resources. It is easy for a company to start an integration project with a “vision”, and stakeholders will begin to expect more and more from it and request you to add customisations and extra features that were not previously discussed. They will want you to get it done faster than the team had planned while working on the same budget that you started with. The result? The project timelines are changed, the budget is strained, and the team is confused about what to expect and why.

Unrecognised complexity

Although this may seem obvious, the complexities involved in each of the to-be-integrated systems are often underestimated by the people involved in the initial project scoping phase. Overlooking critical details would lead to incorrect planning and scoping of the project. The lack of appropriately allocated budget and resources for analysis leads to an inadequate system design being implemented, resulting in a much more expensive and time-consuming process than originally anticipated.

Another pain point in an integration project is that not all to-be integrated processes are automated. There are still some manual steps somewhere which are not identified by or communicated to the delivery team. This poses an increased risk for errors and bottlenecks. New functionality may also need to be developed to bridge the gap in the process. Such work should be appropriately scoped and planned.

There are many factors at play when you connect two different systems with their own APIs. Inevitably at some point, something will go wrong. The data may not match the scheme defined, a connection error may occur, and so on. It is crucial to have an error-handling process in place to manage these issues and prevent errors from propagating to other parts of the organisation.

False assumptions about API

Modern systems very often expose their integration interface as RESTful APIs so that other applications can connect with them more easily. However, in most cases exposing API for communication will not provide the desired outcomes as you are not providing a solution to the integration problem. Instead, you are simply pushing the problem to the integrating parties.

If you don’t know how to integrate with other parties, don’t expect them to understand how to connect with your system either. APIs are great, but only for those who understand how integration processes work.

Unclear accountability

Integration projects typically involve multiple stakeholders having different priorities, conflicting interests and requirements. For example, the sales department may have entirely different integration requirements than the finance department, and the delivery team usually sit in the middle of all this, trying to keep everyone happy without understanding the objectives of the project as a whole. The project might be a nuisance more than a benefit for individual stakeholders.

It is vital to define the person who will be ultimately responsible and accountable for the integration project. This person needs to have the power to take the final decisions between conflicting interests.

Environment and technology changes

In today’s market landscape, to cope with the ever-increasing pace of competition, business applications hardly stay the same. Constant change is a norm rather than an exception. Yet, many integration projects are designed based on a snapshot of the state of the integrating systems. Such an approach fails to keep up with the ever-changing business landscape. This is especially true for projects where the application to be integrated is under development itself. The initial designs are quickly rendered obsolete due to the rapid rate of development. Integration projects require constant changes to keep up with these changes. Not being able to do so would only result in extra costs and lost time for all parties involved.

The big bang approach under unrealistic deadlines

Rolling out several services, applications, or features at once is never the best idea. Many companies rush to develop software as soon as they learn about the numerous advantages and cost-saving possibilities. Business leaders tend to oversimplify the system integration process. This is especially the case if they are unfamiliar with the day-to-day operations that keep their business afloat. They don’t anticipate the employee resistance that might come up as employees might have different priorities. As a result, they may skip critical steps such as business process re-engineering.

Types of integration

Organisations rely on more IT systems and applications than ever to successfully run their businesses. According to a recent report, the average number of software as a service (SaaS) applications used by organisations worldwide has jumped over 1,300% in six years (from 8 in 2015 to 110 in 2021). Various types of integration are essential to provide the business with advanced capabilities.

Application integration

Application integration is the process to enable independently designed applications to work together. It usually involves sharing, aggregating, transforming, or enriching data between multiple applications. However, few of these applications can natively connect to each other. That’s where custom integration solutions come in.

Service integration

Service integration is the technology and methodology used to ensure two or more services can operate together in a truly united manner, collaborating over the delivery of services and seamlessly sharing data, information and knowledge. It merges, combines or automates the workflows of multiple services. With unified workflows and user interfaces, productivity and efficiency can be improved.

Information integration

Information integration, also known as data integration, offers uniform access to a set of heterogeneous data sources. It involves consolidating, deduplicating, transforming, or enriching data from structured, semi-structured or unstructured resources. This is to meet the information and analytical needs of applications and business processes. It eliminates the need to copy, reformat, and cleansing of data before analysis can happen.

Process integration

Business process integration (BPI) allows companies to connect people, data and applications. It is often implemented for complex processes that span multiple departments in an organisation. It is to coordinate internal and external parties for better operational efficiency. The lack of process integration hinders productivity and creates more work for employees. They waste time navigating between systems and copying data from one source to another.

Integration guiding principles

Several guiding principles have been derived from empirical research studies and reports on failed integration projects over the past 50 years. Such principles define the root causes of related, subsequent events.

The principle of business alignment

Alignment of business strategies for the organisation and the stakeholders results in better outcomes for integration.

The integration plan should align with the strategies of the business in which the project is supported. Knowing the needs of the integration project and how those needs are supported by the organisation and the stakeholders is important to the success of the project. The delivery team spend a great effort working with stakeholders to determine requirements and verify that the deliverables satisfy the requirements. Presumably, the requirements satisfy a need and solve a problem for the stakeholders.

The principle of limitation

Integration is only as good as the architecture that captures the business requirements.

For those engineers and architects who have experience creating solutions, they know how challenging it is to prepare an optimum architecture design based on the inputs of key stakeholders. The solution architects must work with very little information and interpret conflicting information. That’s why not all the anticipated benefits of an integration project go into the architecture design. Nevertheless, architecture design is a key ingredient for successful integration planning in which the relations between components in the architecture must be identified and summarised through their connectivity, coupling and interactions.

The principle of boundary

A complex problem is tractable if and only if the boundary of contexts is clearly defined.

KISS is a software design principle which emphasises simplicity. A key objective in programming is to control complexity. Our capabilities are limited by the number of details that we can keep straight in our heads. When we make changes in a complex system, we hardly understand the rippling effects propagating in the whole codebase of that system and all other systems integrated.

Simplicity is often achieved by decomposing a complex system into multiple components. The ease of integration is facilitated if and only if the context boundaries are clearly defined.

The principle of impact

When two systems are integrated, both systems give up some measure of autonomous behaviour and are restricted in some ways to operate.

It is a fundamental question of how much autonomy of both integrating systems you are willing to give up to sustain the operations of the integrated systems. One must identify what flexibility is sacrificed in the individual systems. An integration project brings about challenging issues such as joint operations, joint interoperability, and the degree of control of the integrating systems. It also needs to achieve the required system stability, performance, and functionalities.

The principle of planning

Integration planning is predicated on deterministic scheduling and ad-hoc scheduling.

Planning requires knowledge of which tasks are to be completed and how long the tasks will take to complete. The key issue is in determining the type and amount of resources, the delays to complete the task due to internal and external factors, and the overall impact of missing a scheduled milestone.

Deterministic scheduling is the planning of tasks whose durations are known. Such planning can be optimised for costs or time by ordering the tasks in a particular sequence. Another type of planning involves on-demand or ad-hoc tasks that are unexpected and make the overall project planning more uncertain. By the nature of integration, work is designed to be iterative in a way to wait until testable deliverables are available, ad-hoc scheduling happens which may make planning chaotic. One example is that one system is ready for integration but the integration test is postponed because its counterpart system is not ready for integration yet. One way to handle this problematic scenario is to proceed integration test against an interface that matches the as-yet-completed system.

Types of interaction between integrated systems

We mentioned increasing the simplicity of a design by decomposing and defining a clear boundary between integrated systems. One way to achieve that is by isolation. That is by not sharing internal states or data of a system with others. To communicate or interact, a system may use one or several types of the following: queries, commands, and events.

Queries

Queries are a request for information from another system. An example of a query is to retrieve a list of the latest LinkedIn posts that are related to me. Queries are free of side effects. The system accepting the queries does not change its state. Queries are considered the simplest integration interaction.

Queries are mostly implemented as RESTful APIs because of their synchronous request-response nature. In some use cases, queries are implemented in an asynchronous, non-blocking fashion, which offers increased scalability and reliability in a distributed environment. However, it is important to consider the consistency guarantees for queries. In an event-driven architecture, query results may not be consistent as there might be commands that have not been completely processed.

Commands

Commands are requests that ask the receiver to do something. The internal state of the receiver, and sometimes its dependencies, will be changed as a result of executing a command. Consistency is often a concern regardless of whether to execute a command synchronously or not. A command may cause inconsistencies as it might involve changing the states of multiple objects in one system or its dependent systems. In some use cases, we also want to ensure the idempotency of the commands. One must design an integration solution to process command changes for executing once. In the most complicated scenario, certain commands need to be processed in an orderly manner. The implementation of commands is typically more complex than that of queries.

Events

An event is a representation of something that happened in the past. An event producer may use events to communicate with multiple event consumers. Thus, events should not be tailored for a specific need of a system. Such low coupling enables the highest degree of flexibility for the integrated systems. You may consider events as notifications as they only carry information about something that happened. It is the responsibility of the receiver side to decide what, when and how to act upon receiving them.

Interaction patterns

Integrated systems interact with each other to accomplish specific goals, giving rise to diverse interactive styles and patterns for communication between systems. The basic patterns for exchanging information in integrated systems are detailed in the following sections.

Request and response

In this pattern, a requester system sends a request message to a receiver system, which processes the request and ultimately returns a message in response. This enables two systems to have a two-way conversation with one another over a channel.

Typically, the requester sends a request and waits for a response or a time-out happens. The receiver system receives the message and responds with either a response or a fault message.

Fire and forget

In this pattern, the message sender system is not affected by the unavailability of the receiving systems. Fire-and-forget pattern enables the sender to be completely decoupled from the receivers. A common implementation is to push a message into a queue which is responsible for ensuring its delivery. This pattern helps integration design achieve high scalability and reliability.

Batch-based and real-time data integration

When it comes to big data, there are two main ways to process information. The first, more traditional, approach is batch-based data integration. The second is real-time integration. Batch-based data integration involves collecting a series of data and moving it at scheduled periods or until a given quantity of data has been collected. In some use cases, it is more efficient to process information in batches rather than working with each small piece of data individually. In contrast, real-time data integration involves processing and transferring data as soon as it is collected, with results available virtually instantaneously.

Common integration patterns

Getting integration right is one of the most important aspects of any enterprise project. Do it well, and your systems retain their autonomy, allowing you to change and release them independent of the whole. Get it wrong, and disaster awaits. After all, integration projects have to deal with these fundamental challenges:

- Communication channels are unreliable or slow

- Different systems use different technology stacks

- Change is inevitable

In the book “Enterprise Integration Patterns” by Gregor Hohpe, several integration patterns have been illustrated under four main categories.

File transfer

Managed file transfer (MFT) has been around ever since the early stages of enterprise integration. The file format, standards, location, privileges and read/write coordination must be negotiated between the two systems beforehand. Rarely, the file output from one system is exactly what is needed for another system, so we will have to do a fair bit of processing of files along the way. As a result, standard file formats have grown up over time. Mainframe systems commonly use data feeds based on the file system formats of COBOL. Unix systems use text-based files. Modern systems use XML and JSON. There are many different readers, writers, and transformation tools that have built up around each of these formats.

Shared database

Database integration is a very common form of integration. If other systems want information from a system, they reach into the database. And if they want to change it, they reach into the database! This is really simple when your first think about it, and is probably the fastest form of integration to start with, which probably explains its popularity. This is a common enough pattern, but it is one fraught with difficulties.

First, we allow external systems to view and bind to internal implementation details. The data and its structures are shared in their entirety with all other systems with access to the database. If I decide to change my schema to better represent my data, or make my system easier to maintain, I can break my integration. This type of integration normally results in requiring a large amount of regression testing.

Second, the integration is tied to a specific technology choice. Perhaps right now it makes sense to store data in a relational database, so the integrated systems use an appropriate, database-specific driver to talk to it. What if over time we realise we would be better off storing data in a non-relational database? Likely not. We really want to ensure that implementation details are hidden from the integrated systems to allow our system a level of autonomy in terms of how it changes its internals over time.

Finally, let’s think about the system’s behaviour. There is business logic associated with the data and such logic is going to be changed over time. If the integrated systems are directly manipulating the database, then probably they have their own logic associated with the data. If I want to fix a bug or change the behaviour of the logic, I will need to do it for all the integrated systems, and deploy those changes too.

Remote procedure calls

Remote procedure calls (RPC) refer to the technique of making a local call and having it execute on a remote system. There are several different types of RPC technology out there. Some of this technology relies on having an interface definition such as SOAP. Other technology, like Java RMI, calls for a tighter coupling between the client and the server, requiring that both use the same underlying technology but avoid the need for a shared interface definition. All these technologies, however, have the same characteristic in that they make remote calls look like local calls when they are not! With RPC, I probably should not make a large number of calls without worrying about the performance and the network’s reliability. The core idea of RPC is to hide the complexity of a remote call while there is accidental complexity associated with its implementation.

RESTful API

REST is an interaction style inspired by the Web. Most important is the concept of resources. The server creates different representations of its resource on request. How a resource is shown externally is completely decoupled from how it is stored internally.

As REST has become more popular, so too have the frameworks that help us create RESTful APIs. However, some of these tools trade off too much in terms of short-term gain for long-term pain. For example, some frameworks actually make it very easy to simply take database representations of objects, deserialise them into in-process objects, and then directly expose these externally. The increase of coupling between integrated systems promotes far more pain than the effort required to properly decouple the systems.

Messaging

With message-based integration, all systems connect to a unified messaging bus and exchange data or invoke functionalities via messages. It allows complete decoupling of systems and enables high-speed, asynchronous or synchronous, system-to-system communication with reliable delivery.

Asynchronous messaging designs are powerful, but require us to rethink our implementation approach. Some developers spend an age implementing more and more of the behaviours that you get out of the box with an appropriate message broker middleware. As compared to the other integration approaches, relatively fewer developers have had exposure to messaging systems. Asynchronous event-driven architectures can lead to significantly more decoupled, reliable and scalable systems, but they can also lead to an increase in complexity. One example is to avoid a catastrophic failover from happening.

You should be warned by the associated complexity with event-driven architectures and asynchronous programming in general and be cautious in how eagerly you start adopting these ideas. Ensure you have good monitoring in place, and strongly consider the use of correlation IDs, which allow you to trace requests across process boundaries.

A domain-driven approach to integration

It is usually challenging enough to understand how an individual system works. By integrating two or more systems, we increase the complexity of the task and we need a way to decompose the problem and turn it into more understandable and manageable pieces. Good integration is scalable, reliable and adaptive to changes. One technique to understand and reduce complexity and create a good integration solution is Domain-Driven Design (DDD).

DDD approach is a way to separate the various contexts and draw clear integration boundaries between them. It naturally allows each integrated system to maintain its context domain, using its business language to describe the data and operations that are meaningful to that system. Specifically, it supports the concept of Bounded Contexts. Practically, it means that each domain exposes only well-defined data models and interfaces for interaction with other domains.

Boundaries

Bounded Contexts serve not only as conceptual model boundaries but also as physical boundaries of the integrated systems. Each bounded context should be implemented as an individual project, meaning it is implemented, evolved, and versioned independently of other bounded contexts. Clear physical boundaries between bounded contexts allow us to implement each bounded context with the technology stack that best fits its needs. That said, bounded contexts themselves are not independent. Just as a system cannot be built out of independent components - the components have to interact with one another to achieve the system’s overarching goals. Although they can evolve independently, they have to integrate with one another. As a result, there will always be touchpoints between bounded contexts. These are called contracts.

Integrating bounded contexts

Since each contract affects more than one party, they need to be defined and coordinated. Also, by definition, two bounded contexts are using different ubiquitous languages. Which language will be used for integration purposes? These integration concerns should be evaluated and addressed by the integration solution design. In the next sections, we will go through each of the common approaches to define contracts for integrating bounded contexts.

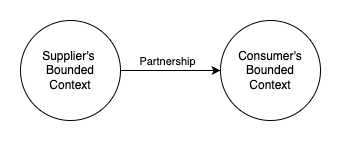

Cooperation: Partnership

In the partnership pattern, the integration between bounded contexts is coordinated in an ad-hoc manner. One team can notify a second team about a change in the API, and the second team will cooperate and adapt. No one team dictates the language that is used for defining the contracts. Both teams cooperate in solving any integration issues that might come up.

This pattern might not be a good fit for immature Agile teams or geographically distributed teams since it may present political issues blocking the integration or communication challenges.

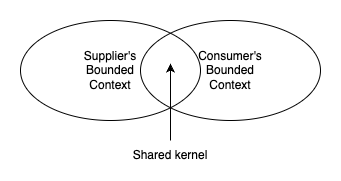

Cooperation: Shared kernel

In this pattern, common models are defined and shared across all bounded contexts that are using it. A change made to the shared model has an immediate effect on all the bounded contexts. Hence, to minimise the cascading effects of changes, the overlapping model should be limited, exposing only that part of the model that has to be implemented by both integrated bounded contexts.

When to apply the shared kernel pattern depends on the trade-off between the cost of duplication and the cost of coordination. Since the pattern introduces a strong dependency between the participating bounded contexts, it should be applied only when the cost of duplication is higher than the cost of coordination.

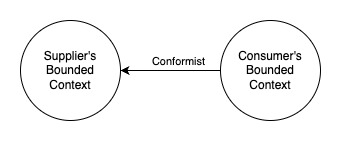

Customer-supplier: Conformist

Unlike in the cooperation patterns, in customer-supplier patterns, the power of the integrating teams is imbalanced. Either the upstream (the service provider) or the downstream (the service consumer) team can dictate the integration contract.

Sometimes the upstream team have no interest in supporting the downstream team’s needs. The upstream system would expose the integration contract defined according to its own model. The power imbalance can be caused by the integration with external service providers or simply by organisational politics. If the downstream team accept the upstream’s contract, it is called the conformist pattern.

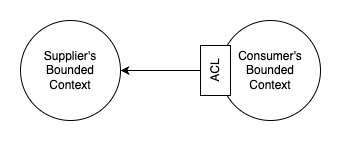

Customer-supplier: Anti-corruption layer

The anti-corruption layer (ACL) pattern is similar to the conformist pattern in that the balance of power favours the upstream team but the downstream team do not conform. Instead, an anti-corruption layer is created for transforming the upstream model into a model tailored to its needs. The ACL isolates the downstream system from a different bounded context that is not relevant to it. Hence, it simplifies the downstream system’s model.

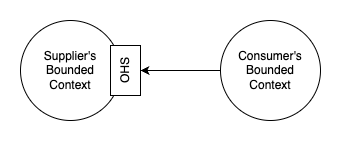

Customer-supplier: Open-host service

The open-host service (OHS) is the opposite of ACL. In this pattern, the power is skewed toward the downstream consumers. The upstream supplier system provides a decoupled model that is different from its internal implementation. This decoupling allows the supplier and the consumers to evolve their implementations at different rates. The integration interface exposed by OHS is intended to make it convenient for the consumers without affecting the downstream contexts when the upstream implementation changes.

Separate ways

The last integration approach is not to integrate at all. This can be due to different reasons, in cases where the teams are unwilling or unable to cooperate due to the size of the organisation or internal politics. In that case, it might be more efficient to duplicate the functionality of another system rather than integrate it.

Conclusion

We have reviewed the common pitfalls and challenges when implementing an integration project. Some common integration patterns and the use of domain-driven design were introduced and explained. As system integration is key to delivering values with a software project at its full potential, an appropriate integration strategy at its disposal prepares an organisation to take on customer expectations with utmost confidence. As a premium service provider, we provide the requisite expertise to scale up the business to grab the opportunities coming.

30 Aug 2022 by Alan Tai