Because it matters

Making things happen, making things right, because it matters.

9 tips for estimating software project proposals

QuickDraw is the 2D graphics library written entirely by Bill Atkinson in the 1980s. Andy Hertzfeld considers it the single most significant component of the original Macintosh technology. It consists of a total of 17,101 lines of code in assembly language. During a magazine interview, Bill remembered that he worked on it on and off for four years. Steve Jobs told the magazine reporter that it was 24 person-years Apple had invested in QuickDraw.

Is that how we cope with the impossible project deadlines due to poor estimates which are sometimes off by a factor of 3 to 10? How could we estimate more accurately such that we don’t have to hire 10x engineers to rescue the project?

All software project proposals I helped to create involved a certain degree of risk and pressure. The risk and pressure come from multiple sources — the business environment is chaotic, the project schedules are so compressed, the budgets and people assignments are so constrained, and at the same time, we want our offers to be as competitive as possible. For Software Engineers who are asked for the first time to provide estimates for a project proposal, it is like being asked to overcome impossible odds and achieve miracles.

The Mythical Man Month is arguably the most influential book ever published about software estimation. Project managers and developers have been relying on its advice for the past half a century. Yet, this book was not written specifically for estimating proposals. For instance, one must estimate upfront without gathering all requirements. It is often not possible to ask the potential client to spend 20 hours sitting with the development team to answer 200 clarification questions about the stated requirements. How is that possible to answer the question about how much time it takes to deliver a certain feature without knowing the requirement details?

The following secrets are what I have learned from the trenches to succeed in estimating proposals.

Estimates are not commitments nor targets

What would the estimates you provide be used for? Unlike sprint planning, where we estimate story points for individual stories or tasks so that we can plan accordingly, we estimate the time effort to deliver modules, epics, and the entire project for a proposal for multiple purposes. A business has limited budgets, resources and time to achieve a desirable goal. There are important reasons to set business targets but that doesn’t mean they are achievable and so estimates should be independent of targets.

For cost estimation

Austria law demands that if you give a customer an estimation of the cost, you are only allowed to miss that by +15%, otherwise the customer can terminate the contract and pay for the work done so far. Many other countries don’t have a similar law, but the consequences of underestimating a proposal can be as damaging, if not more serious.

It is crucial for a consulting firm to accurately estimate the cost of delivering a project. However, don’t be confused by mistaking cost estimations as commitments. A commitment is a promise to deliver defined functionality at a specific level of quality by a certain date. Notice that the keywords are not only the date but also functionality and quality. Any projects that require more than 3 months of work often go unpredictably. The business environment changes, the people change, and the needs and requirements change. Insisting on delivering an agreed functionality when the needs change doesn’t make sense to the business. Things will change and we commit to delivering maximum business value rather than outdated predictions.

For scope estimation

Usually, we get a better understanding of the project scope through the exercise of estimation. We are forced to think of unstated requirements, non-functional requirements, and all other necessary activities that take time. It is important for service providers to decide whether it is a manageable scope that is worth proposing or if the scope is too big or risky and they should give up.

For time estimation

Most customers, if not all, need to know by when a certain amount of business value would be delivered. Agile projects run iteratively, organised in phases, and the business value is defined by the reached milestones. The reason why software projects use an incremental approach is that we are supposed to re-estimate after completing a phase to adopt changes. We know that the initial estimation before a project starts will never be true by the time when the project ends.

That’s why when you are asked for a time estimation for a proposal, you are expected to provide an order-of-magnitude estimation. Don’t go too far by digging into every detail of the requirements. How many times have you estimated accurately, within 10% of error, the time needed to complete a 3-point story? Rarely, if not never. It will take you days trying to clarify every requirement detail, and it won’t work.

For people assignment

Similar to scope estimation, service providers need to estimate, plan, and project into the future if they will have the right people with the required skillsets for the job. As people are the most essential asset and the most expensive cost to a consulting firm, one has to carefully estimate the project schedule and technical stacks and come up with appropriate staffing requirements.

An estimate is not a single number

I had a customer who wants to build an app that offers a metaverse game-like experience. The target is 6 months. The customer showed me a page with a dozen boxes on it labelled with the name of the functionalities of the app such as “user login” and “claim and spend rewards”. Below the boxes is a few bullet points specifying how the app should behave in the metaverse. I was asked to provide estimates, including the project cost and team size, on the spot based on the information on that page. “All the details are on the list and just keep it simple for the rest of the things”, the customer added.

There is no way I can estimate like this, nor anyone. If I must provide a number, it must be a random number. I need much more information than one page to estimate with an error rate of less than 1000%. Later we found out that the customer wanted the app to provide biometric and one-time passcode authentication. That led to the question of whether to use a cloud service to provide the OTP functionality or to build it in-house and based on the customer’s security requirements, whether we want to keep the OTP encryption key on a dedicated HSM or shared key infrastructure.

To get a useful estimate, we need a certain level of details of the requirements. The Law of Large Numbers tells us that if an estimate I provide is off by ±X%, the average error rate of a large number of estimates will be smaller than X% because the errors tend to cancel each other out to some degree. There are two ways to generate a large number of estimates — to ask a large number of engineers for estimates, or to break down large requirements into smaller ones and estimate every one of those. The first approach is typically not feasible so it is preferable to take the second approach. You may ask, “how many and how small should the requirements be?” It depends on your target estimation error rate. If a small error rate is desired, you should take an agile approach, deliver the project incrementally and re-estimate frequently.

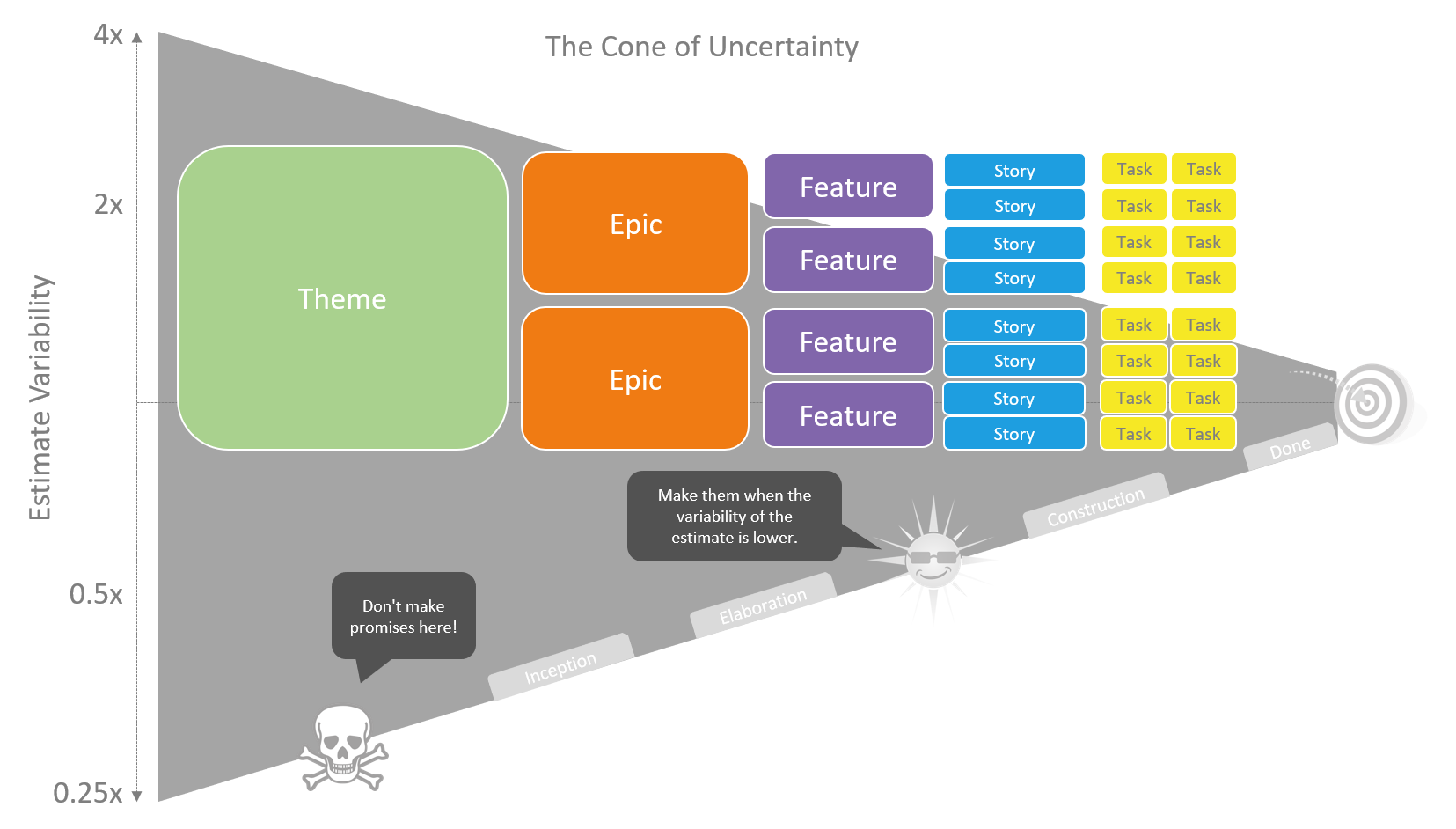

Be aware of the Cone of Uncertainty

It mostly takes about 50 minutes for me to get back home from the office. I always take the same route at the same bus stop at a similar time. Sometimes it takes up to 65 minutes for some reason. If I tell my wife I’ll be at home in 50 minutes, I’ll be off by 30% occasionally. Once or twice a month, it takes up to 80 minutes to travel which is equal to 60% of error and my wife would not be happy.

Building software involves many more variables. It’s not uncommon that estimates are off by several hundred per cent at the beginning of a project. It is widely suggested to defer estimation when the team have better visibility of the project and its variability becomes lower. This won’t work for estimating proposals as one must estimate upfront. An alternative approach is to lower the variability by asking yourself what you could deliver instead of asking the customer what is required to be delivered. There will only be two outcomes with this approach. One outcome is that the customer is happy with what you proposed. The other one is that now there is a better understanding between you and your customer as the gaps in requirements are identified which enables a more accurate estimate.

Estimate everything, not just coding and testing

There is a joke among Project Managers that when a developer gives an estimate, multiply it by 3 and you will get the actual time needed to get things done because developers keep forgetting the time for sleeping and eating.

It is true that when we estimate, we tend to forget to include many other necessary tasks and activities. There are usually many unstated or implied requirements that the customer expects us to know including functional and non-functional requirements and other project activities. Some of these are listed below.

- Unstated/implied functional requirements: Knowledge transfer sessions, data migrations, documentations, and system integrations

- Unstated/implied non-function requirements: Security, usability, observability, and other “ilities” such as scalability and performance

- Forgotten project activities: Team onboarding such as waiting for a git account permission approval, requirement clarification meetings, waiting to get permission to provision deployment environments, getting support from the infrastructure team from the client side when an environment is down, demonstrating software to stakeholders and repeating it once or twice for those not able to join previously, and the delays in getting a hold of someone from the client side

Estimates don’t scale linearly; they scale exponentially

Ants can carry objects of up to 20 times their body weight while humans can only do it up to 1.5 times our weight. The strength inverse exponentially correlates to the size. It’s the square-cube law that governs such behaviour. In software project management, we have Brooks’ law that defines a similar relationship. Let’s say you have previously done a project with a team size of 10. The next project is going to be a 100-people team with 10 times more features to develop. The estimate for this project won’t be 10 times but a lot more. When the number of people involved in the project increases, the complexity of interactions between people increases exponentially.

There is one approach to reduce the impact of the exponential growth in estimates. We can define good communication boundaries to minimise interactions between modules as well as people.

Don’t let uncertainty affect your ability to estimate

The requirements are always lacking to estimate a proposal. Chances to clarify requirements with the customer are rare, especially when it is a large project with a sizeable number of competing service providers. The key in proposal estimates is to express the uncertainty. This allows us to communicate uncertainty with the customer. Be sure to express estimates as ranges, showing the best-case and worst-case estimates. The customer would be interested in knowing under what conditions the best-case estimate would be true and the same goes for the worst-case estimates.

Expressing uncertainty using a set of best-case and worst-case estimate ranges is one of the ways to narrow the Cone of Uncertainty. Single-number estimates given by engineers tend to be close to the best-case estimates, which is often unrealistic. Estimating for the worst case would force them to be less optimistic and try to include estimation for those things that are often forgotten otherwise.

Estimates are based on assumptions

Stakeholders and engineers make a lot of decisions before and during development. Some of these decisions have a significant impact on the development effort and time. When estimating a proposal, one must also make “decisions”, or assumptions as these decisions are not confirmed, for proposal estimates. It is essential to embody assumptions in the estimate. Assumptions usually include:

- Which (unstated/implied) features are required or not required

- How long it would take to clarify requirements or get technical support from the client

- Availability of key resources and people

- Features and tasks dependency

There will always be some wrong assumptions. In that case, it allows us to clarify such assumptions with the customer.

Don’t tweak estimates; tweak the requirements

From my experience, when people don’t feel right with the estimates, it tends to put more pressure on tweaking the estimates than the requirements as there is always a business target to meet. Estimates given by engineers are often closer to the best-case scenario than the worst case. It would not be wise to compress the estimates further without first re-visiting the requirements and the assumptions made.

Remember that the only way to narrow the Cone of Uncertainty is by removing the sources of variability. We should clarify requirements wherever possible, otherwise, we can make design decisions and assumptions that would make a project more predictable.

Estimate what you can deliver if you cannot deliver what is required

No two software projects are the same. There are always some requirements of a project you have never done before and you don’t know how to fulfil them. Instead of giving up proposing a solution that complies with all the requirements, proposing a solution that doesn’t comply, surprisingly, might also work. This is because what the customer is looking for is not software that fulfils all the requirements. The customer wants to generate business value with the software you deliver.

There is often more than one way to deliver the desired business value without working as the requirements specified. Try to tweak the requirements to something you are confident in estimating and delivering. The customer may love it!

05 Aug 2022 by Alan Tai